This entry will focus on three overlapping and reoccurring iconic themes that appear in Chicano and Chicana art: ancestral emblems, Catholic Church symbols, and figures from popular culture.

The terms Chicano and Chicana are specific to the identity of Mexican-Americans born and living in the United States and within Chicano art, icons are used to represent Mexican culture. The Chicano/a movement took place during the 1960s and 1970s, was when the search for identity was the focus for many artists (Traba, 1994). This search for identity is reflected in Chicano/a art, whose goal broadly defined is to translate Mexican culture for a broad audience.[1] As understood today, an icon is an image that signifies something beyond its visual presence and is universally identifiable (Sturken, 2001). Many artists seek to reclaim their heritage and culture through the use of icons which can take the form of symbols, signs, cues, or totems and in this case translate Chicano art to a broad audience.

Sharing ancestral traditions and the spiritual beliefs of Mexican culture is an important part of the Chicano/a movement. During the 1960s, modern Mexican artists living in the U.S. sought to express their mixed cultural identity, lost through centuries of colonialism (Traba, 1994). Artists rediscovered and reclaimed their culture through Chicanismo, which shared aspects of the narratives of pre-Columbian Mexican culture (Sullivan, 2011). Chicano artists assimilate ancestral and spiritual icons, such as Mayan and Aztec symbols, including Tezcatlipoca who was an Aztec goddess, the Pachamama who symbolizes Mother Earth, and skulls which are emblematic of the Mexican Day of the Dead. These icons not only refer to the knowledge of ancestral and spiritual traditions in Mexico, but serve an important function for Chicano/a artists in remembrance of those who shaped and shared Mexican culture.

Ancestral emblems appear in Chicano art in various forms. For example, the artist Eva C. Pérez chooses stone sculpture as her medium because it was originally the material used by her ancestors. Pérez believes working with this medium brings her closer to her ancestors and enriches her pride in being Chicana (Keller, Erickson and Johnson, 2002). In this case the iconic symbol is the medium. By sharing the icons of Chicanismo, artists are returning to their origins in a continued tradition of passing on the knowledge of their culture to others.

The Roman Catholic Church is a major theme in Chicano art because it symbolizes colonization by Spain. Early Spanish colonizers in Latin America forced their way of life, belief system and religion onto the Mexican people. The Virgin Mary, also known as the Virgin of Guadalupe, and the sacred heart of Christ are reoccurring Catholic icons in Chicano art. The Virgin of Guadalupe is a key figure for the Catholic Church, representing Mexican nationality, spirituality, and for many Mexican women a role model (Keller, Erickson and Johnson, 2002). The sacred heart of Christ represents love, suffering, compassion and the redemption of sins (Keller, Erickson and Johnson, 2002) and Chicano artists such as Yolanda López are renowned for appropriating this Catholic icon.

Another means of working with Catholic icons within Chicano art is creating hybrid forms by mixing references to Catholicism and with references to indigenous traditions in Mexico. This custom parallels the evolution of the Catholic Church within Latin America. Raúl Paulino Blatazar and José Esquivel are artists who create aesthetic hybrids combining imagery from the Mexican Revolution and emblems of Mayan culture with references to Christ and the Virgin of Guadalupe. Icons from the Catholic Church are easy to identify by those familiar with the icons of the Christian faith making it easy for their audience to see the irony in these artists’ work.

Ranging from comic characters to political figures from Mexico or North America, popular culture icons communicate through their audience’s familiarity with mass media. Some of their art incorporates text, hinting at advertising from popular culture media (Sturken, 2001). Mexican popular icons that are portrayed include stereotypical images of Mexicans sporting sombreros and moustaches, the masked Mexican wrestlers known as luchadores enmascardos, the Revolutionary hero Pancho Villa and other Latin Americans such as Che Guevara. These are icons that people outside of Mexico associate with the identity of Mexican culture. For some Chicano artists, exaggerated stereotypes confront the viewer with their racism towards Mexican settlers in the United States (Vargas, 2010). This is especially evident in the works of Guillermo Gómez-Peña, Coco Fusco, and Xavier Garza, all of whom live in the U.S. North American icons that appear in Chicano art also include cartoon characters such as Mickey Mouse, American presidents and well-known figures from both World Wars, the Korean War and the Vietnam War. Appropriations of these icons can also be seen in the works of Richard Álvarez, Carlos Callejo, and Ignacio Gómez who incorporate traditional Mexican figures within their works. Mixing references is an important aspect of Chicano art for many because it emblematizes and characterizes the fusion of Mexican and North American culture.

Matilda Oja

Notes

[1] In the Spanish language, general grammatical terms are written in male tense – ending in an ‘o’– rather than an ‘a’ which denotes the female tense.

Works Cited

Keller, Gary D., Erickson, Mary, and Johnson, Kaytie, Alvarado. Contemporary Chicano and Chicana Art: Volume 1. Tempe, Arizona: Bilingual Press, 2002.

Keller, Gary D., Erickson, Mary, and Johnson, Kaytie, Alvarado. Contemporary Chicano and Chicana Art: Volume 2. Tempe, Arizona: Bilingual Press, 2002.

Sturken, M., & Cartwright, L. Practices of looking: An introduction to visual culture. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Sullivan, E. J. Latin American Art in the Twentieth Century. Hong Kong: Phaidon Press Limited, 2011.

Traba, Marta. Art of Latin America: 1900-1980. Baltimore, Maryland: Inter-American Development Bank, 1994.

Vargas, G. Contemporary Chicano Art: Colour and Culture for a New America? Austin: University of Texas Press, 2010.

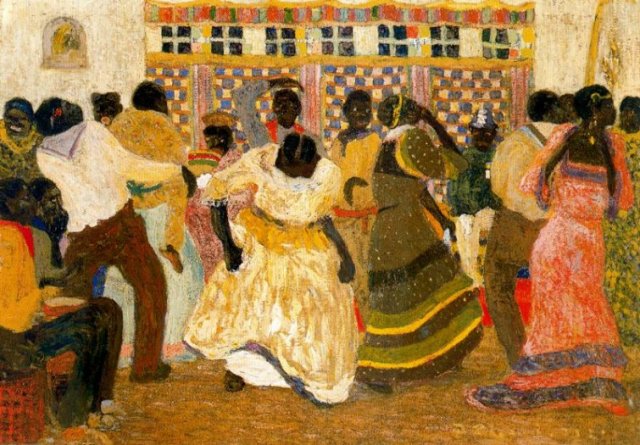

Early twentieth century, artist Pedro Figari (1861-1938) captured the religious movement imaginatively through painting. Many believe that his paintings depict accurately the Candomblé religion to the rest of the world. Pedro Figari was born in Montevideo, Uruguay. Growing up, Figari observed the Afro-Uruguayan community which ultimately inspired him to create over 4,000 paintings motivated by his youthful memories of those practicing Candomblé. Hence a lack of pictures or representations relates back to a struggle of control. Who is free to take pictures? What do the images show or communicate? Which agenda do they illustrate? What purpose do they serve? On a further note about images: As mentioned previously, Afro-Brazilian religion is associated with religion blending between African beliefs and European religion. Powerful priests and intellectuals hold firmly to the traditional belief that Candomblé shrines should not contain Catholic images. These individuals believe that Candomblé and Catholicism are two different things and as such should be kept separate. Candomblé shrines are also considered very personal, with the shrine itself often hidden in the individual’s backyard away from the public eye.

Early twentieth century, artist Pedro Figari (1861-1938) captured the religious movement imaginatively through painting. Many believe that his paintings depict accurately the Candomblé religion to the rest of the world. Pedro Figari was born in Montevideo, Uruguay. Growing up, Figari observed the Afro-Uruguayan community which ultimately inspired him to create over 4,000 paintings motivated by his youthful memories of those practicing Candomblé. Hence a lack of pictures or representations relates back to a struggle of control. Who is free to take pictures? What do the images show or communicate? Which agenda do they illustrate? What purpose do they serve? On a further note about images: As mentioned previously, Afro-Brazilian religion is associated with religion blending between African beliefs and European religion. Powerful priests and intellectuals hold firmly to the traditional belief that Candomblé shrines should not contain Catholic images. These individuals believe that Candomblé and Catholicism are two different things and as such should be kept separate. Candomblé shrines are also considered very personal, with the shrine itself often hidden in the individual’s backyard away from the public eye.

You must be logged in to post a comment.